By Eric Jessen 8/29/09

Samuel Fuller's Forty Guns is covered with annoying clumps of throw-away conventional cinema. But underneath it is a wonderful mock-western. The Arizona 19th century frontier is stripped of its man-on-horse love affairs and macho honor code (Peckinpah-esque) babble. The dusty, hairy and dirty wild west is replaced by a drab, clean-cut town. The cowboys look more like city slickers, as fit to hold a tommy-gun as their Colt-45. The violence isn't overly drawn-out with shifty eyed stare-downs and High-Noon-esque staginess. Instead, it is spontaneous, sometimes anti-climatic and the results (who lives and who dies) of the shootouts and bar-room brawls are unpredictable.

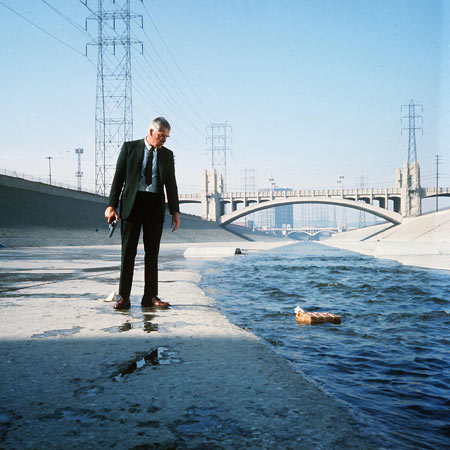

Forty Guns is about U.S. Marshal Griff Bonnell (Barry Sullivan) who is sent to an Arizona town to arrest Howard Swain (Chuck Roberson). When he finds Swain, he learns that Swain is one of the 40 hired guns of local landowner Jessica Drummond (Barbara Stanwyck). Drummond and Bonnel eventually cross paths which leads to a romantic relationship.

Taking the aforementioned clumps into consideration, Forty Guns has its peeks and valleys. There are moments of dull conversation, there are some lame set-ups. But there are also moments of crazy, unkempt activity (real movie-fun), the kind of moments you'll always remember (your brain attaches a mental post-it note). They're great attention grabbers. Samuel Fuller is giving a joyful wink to the audience when he shocks or appalls, when he breaks unwritten rules.

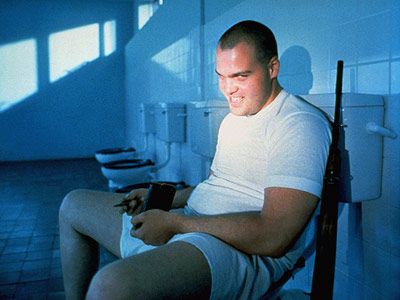

In Forty Guns when Griff Bonnell is confronted by a drunk hooligan, Brockie (John Ericson) who has just terrorized and shot-up the town, don't expect them to take 10 steps in opposite directions, turn and fire. Instead Griff simply walks comfortably towards Brockie, as Brockie screams and threatens to shoot, and then abruptly pulls his gun out of his holster and thumps Brockie over the head. In a Samuel Fuller quiet Arizona town, don't expect a peaceful wedding: as the picturesque newlyweds share a first kiss, the husband is shot down. In Forty Guns don't expect a heart-to-heart conversation to reach its tear-jerking climax, that too is liable to be cut short by gun fire. I cherish all of these great little moments of artless violence. They can be silly or ridiculous but they're always entertaining. And my favorite moment in Forty Guns is the ending (ignoring the final two scenes added on top because the producers disapproved). It's a fantastic slap in the face to westerns. Griff's girl, Jessica, is being held up by one of her 40 guns, Brockie (the same hooligan from earlier). Brockie yells at Griff, “I'd like to see you shoot her!” Then, wasting no time, BANG! Jessica is down, then BANG... BANG... BANG......... BANG! Brockie is dead. Griff walks past them with a cold forcefulness, never once looking down at the two bodies.

That scene brings to mind one other interesting thing about Forty Guns: its phallic love for guns. All the characters in the movie talk about guns with a strange passionate attentiveness. Jessica says to Griff, “I'm not interested in you, Mr. Bonnell. It's your trademark,” pointing to his gun, purring. She then says, “May I feel it?” The trigger clicks... BANG....and they get goosebumps all over. One shot after another from their freshly polished pistol is how they get off. They treat each other like strangers and their guns like a loved one, their one and only companion. At the end when Griff shoots Jessica, he has expressed his deepest feelings for her. Griff shooting Jessica at waist level is their way of consummating.

With Forty Guns, despite its final two scenes, despite some boring characters and listless performances, I can think fondly back on the spontaneous violence and the hilarious covertly sexual dialogue. I love Samuel Fuller the fringe, pulp-movie director. And what I love most is his willingness to shock me.